The role of the SDM(s)

Ontario law requires that healthcare practitioners get consent for treatment from the person (or from the SDM if the person is incapable) to consent to a specific treatment.

- They cannot get consent directly from a document such as an "Advance Directive", "living will", etc.

- Ontario law doesn't recognize such documents as consent for treatment. The only exception is a signed C-DNR form or a DNR form completed in a health care institution.

Therefore, the role of an SDM is to give or withhold consent for treatment or care when (and only when) a person is mentally incapable to make a treatment or care decision.

So the first step is for the clinician who is proposing treatment or care is to establish whether the person has or lacks the mental capacity to make the decision for themselves.

For more information, see Resource Guide.

Priya has advanced dementia. She lives with one of her daughters who is finding it difficult to care for her safely at home. She speaks to their home-care coordinator about long-term care. The coordinator's role is next to determine whether Priya has capacity to make a decision about moving to long-term care.

The home-care coordinator determines that Priya lacks capacity to make a decision about moving to long-term care. Therefore, Priya's SDMs (her daughters) will give consent to complete the application for long-term care.

How to assess capacity?

As defined in the Health Care Consent Act, a person is capable of

giving or refusing consent if s/he:

1. Understands the information relevant to

making the decision about the proposed

treatment.

2. Appreciates the reasonably foreseeable

consequences of both accepting and declining

the proposed treatment.

Capacity is decision and time specific

- Decision specific: A person may lack the capacity

to consent to surgery but retain capacity to make

decisions about long term care placement.

- Time specific: A person may lack the capacity to

make a certain decision today but may regain capacity tomorrow, e.g. delirium, medication side

effects or intoxication.

Read more about assessing capacity

How to identify the person's SDM?

How did Priya's home-care coordinator know who is Priya's SDM(s)?

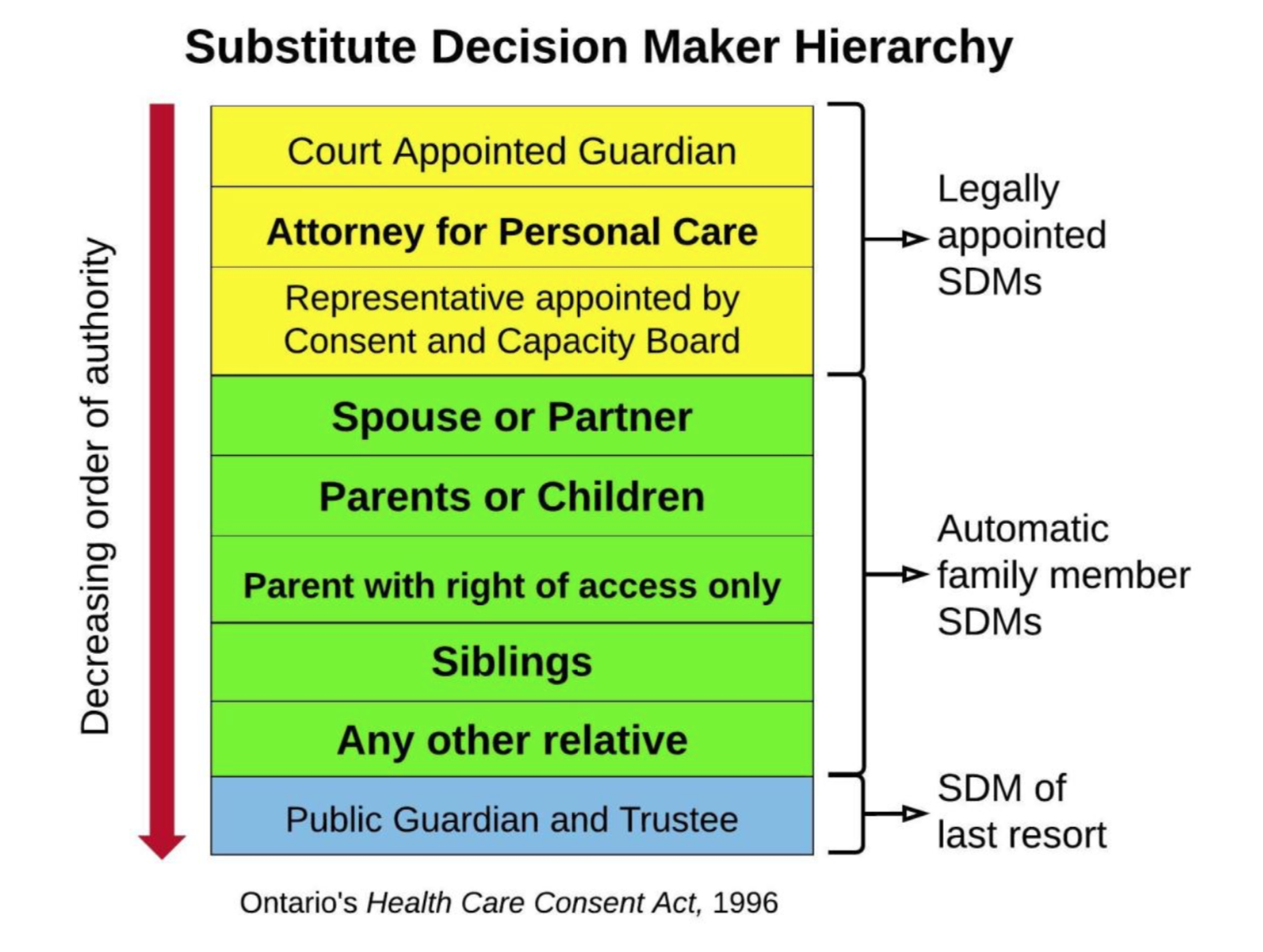

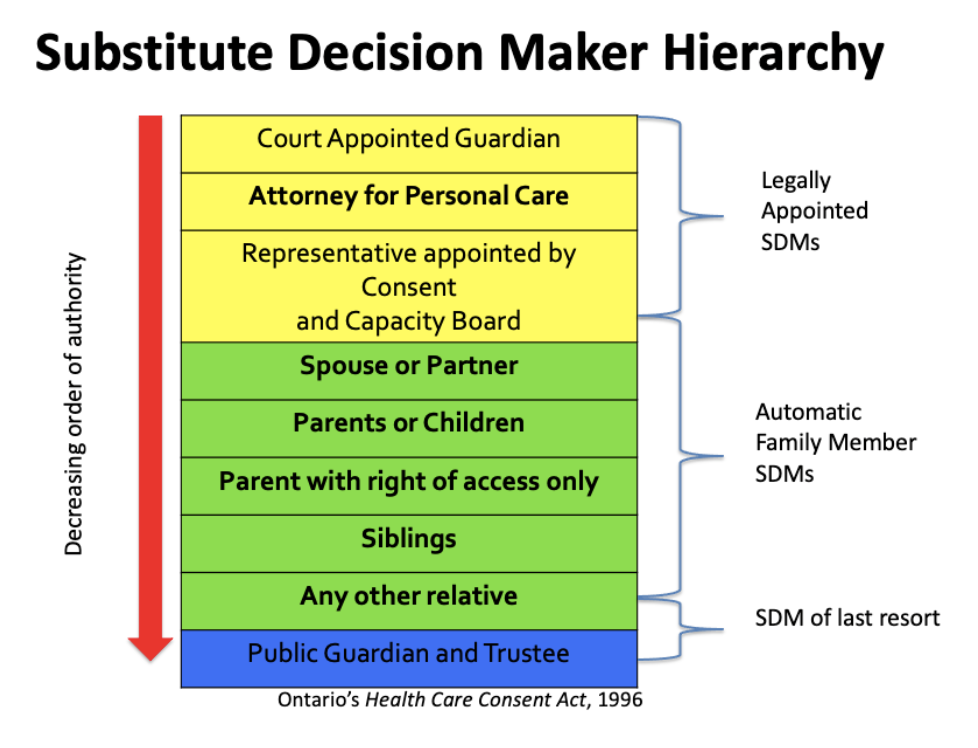

Every clinician in Ontario must know how to determine a person's SDM(s). In Ontario, every person has an automatic SDM outlined in the SDM Hierarchy of the Health Care Consent Act.

The first category (yellow) includes legally appointed SDMs. If someone has legally appointed SDM(s), that person(s) are the correct SDM as they outrank family members.

- Court Appointed Guardian

- Attorney for Personal Care

- Representative Appointed by the Consent

and Capacity Board

If there is no legally appointed SDM, then the second category (green) is where you identify the person's automatic SDM(s). This is the default SDM(s) in Ontario - no-one has to appoint or choose an SDM. This is important to explain to people -- they don't have to actively choose someone, they will have an automatic SDM(s) so it is important to know in case they don't want that person acting as their SDM. The SDM(s) is the highest ranking family member. This is the case for most people.

- Spouse or partner

- Child or parent

- Parent with right of access only

- Siblings

- Any other relative

If a person has no living family members and no-one has been legally appointed as an SDM(s), the Public Guardian and Trustee makes decisions or gives consent to treatment for the patient (blue).

- Public Guardian and Trustee

Althea is not married. Her mother has dementia and can't be her SDM. Her two sister's are her automatic SDMs

Bob has three children. His parents died several years ago. His children would all share the role of his automatic SDM.

Tran is married so her automatic SDM is her husband. Her parents are lower on the hierarchy than her husband or partner.

Jacob's automatic SDMs would be both of his parents.

Priya's is widowed and has three children. Her mother has advanced dementia so not able to be an SDM. Her father died several years ago. So her automatic SDMs are her 3 daughters. They would all share this role.

What if Althea, Tran or Bob didn't want their automatic SDM but wanted to choose someone else?

There are many reasons this might happen - sometimes a person doesn't feel their closest relative will be able to make a difficult decisions that reflect their wishes, values and priorities.

In this case, a person can appoint an Attorney for Personal Care (POA). See next section for how to do this.

You can help them decide by explaining the qualities of a good SDM. See next section for the qualities.

Appointing a Power of Attorney for Personal Care

If a person wishes to appoint someone other than their automatic SDM(s), they simply have to complete a Power of Attorney for Personal Care form. These forms can be found through the Attorney General of Ontario's Office (www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca)

- This is specifically for health care treatment decisions and location of care.

- This form needs to be witnessed, but does not need a lawyer.

- There is a separate process for financial Power of Attorney.

- A person must be capable in order to appoint or change a Power of Attorney for Personal Care.

Qualities of SDM(s)

An SDM should be:

- Willing to accept the role and make health and personal care decisions for another person in the future

- Willing to talk to and understand the goals, values and beliefs of another person

- Willing to interpret, honour and follow the patient’s wishes, values and beliefs as much as possible when they apply

- Able to ask questions and advocate for the patient with the health care team

- Able to make difficult decisions

Additional information about SDM(s)

- Other people can support and assist an SDM in decision-making. SDM(s) can discuss options with other family, friends, spiritual leaders, etc., before making treatment or care decisions.

- When there are multiple SDMs at the same level (e.g. multiple children, multiple siblings or a child and a parent), all names should be listed as SDMs.

- When future decisions are to be made, all SDMs must be consulted to see if each is willing to act as an SDM. When all eligible SDMs are willing, able and available ALL must agree on any decision.

- Even if a person is highest ranking, he/ she may refuse to act as SDM for the person. If that happens, then the Health practitioner may turn to the next highest ranking SDM that meets the requirements.

- It is important to note that an SDM(s) can only consent or refuse a treatment and cannot demand a treatment. It is up the healthcare providers to determine what treatments will be offered based on your health condition.

- If the patient is concerned about possible disagreement among SDMs or if the patient prefers a different individual to act as their SDM, then ACP conversations are a great time to discuss legally appointing an Attorney for Personal Care. (For more info visit www.attorneygeneral.jus.gov.on.ca)

- This can be more than one person but this person or these people would become the patient’s SDM(s)

Althea is widowed. She has no children. Her mother has advanced dementia (aged 96) and lives in long-term care. She is not capable of fulfilling requirements to be an SDM. Althea has two sisters. By hierarchy, both sisters are SDM(s). Althea feels that her eldest sister Sharon would be best able to represent her if she became incapable of making treatment or care decisions. She worries that her younger sister would struggle to make difficult decisions. Althea decides to complete of Power of Attorney for Personal Care to appoint Sharon as her substitute decision-maker.

Prior wishes & best interests: How SDMs make decisions

When an SDM is making a decision on behalf of an

incapable person, s/he must imagine how the

person would have made the decision for themselves.

The Heath Care Consent Act has two rules for SDMs to

follow: 1: Prior Capable Wishes and if none are known, then Best Interests.

Prior Capable Wishes

Prior capable wishes are preferences the person expressed in the past that apply to the current situation. They may be part of an advance care plan, and/or part of the Power of Attorney for Personal Care document. In Ontario, all manners of expression of prior capable wishes are considered valid including verbal, video, Braille, etc. The most recent capable wishes are considered, even if they are not written. When making decisions, the SDM must follow wishes whenever possible if they apply to the decision that needs to be made. Some wishes may be impossible to follow.

When considering prior capable wishes the SDM and healthcare provider may ask:

- Are they applicable to the current situation?

- What would __________ have wanted in this situation? Does acting on this prior capable wish reflect __________’s most recent thoughts, values and beliefs on this issue?

- Will the outcome/decision be consistent with what __________ would want in this situation?

- Is the outcome/decision consistent with what __________ values as important in his/her life?

- Is the outcome/decision consistent with __________’s most recent goals for a good life?

Best Interests

In the event that no prior capable wishes are known or they are impossible to follow, the SDM must consider the best interests of the person. Considering the best interests of a person will involve an exploration of his/her values, beliefs and personal goals. SDMs and healthcare providers will have their own values and beliefs about the situation, but it is the person’s values that must remain central to the decision-making process.

Best interest can be considered by asking:

1. Will the treatment:

- Improve the person’s current condition or well-being?

- Prevent worsening of the person’s condition or well-being?

- Slow down the process of getting worse?

2. Without treatment will the condition get better, worse or stay the same?

3. Do the benefits outweigh the risk of harm? (**risks/benefits as the person would consider them)

4. Is there a less aggressive option that might be as beneficial to the person?

Here is an example of Priya's SDM(s) making health care decisions based on her prior expressed wishes.

Over the past years, before her dementia worsened, Priya told her family that she wishes to be cared for at home -- that she doesn't like being in hospital. She hopes she can avoid hospital trips as much as possible. Those are her wishes to her substitute decision-makers. Those wishes are primary importance if something happens to Priya.

But her wish isn't a decision made in advance and her SDM(s) have to consider the wish in context of a current illness or injury.

One year after being admitted to long-term care, Priya falls. She clearly has fractured her hip. She is in significant pain. The clinician calls Priya's daughter to discuss what to do. Priya's daughter considers her mother's wish to avoid hospital, however, in this case, she decides that going to hospital to manage the broken hip is the best plan of action. Priya's daughter takes her mother's wishes into account, but given these specific clinical events, decides that her mother would choose hospital at this time.

A further year later, Priya suffers a stroke. She is unresponsive and comfortable. The clinician calls Priya's daughter and Priya feels that her mother would not want to go to hospital given this situation where there is little the hospital can do to improve her comfort or reverse what has happened.

Making End-Of-Life Decisions for Others

When we ask SDMs to make decisions for others at

the end-of-life, they not only face what can be difficult decisions, but potentially also saying

goodbye to the person.

Anticipatory grief is a common experience for the

SDM(s) of a loved one who requires end-of life care. SDM(s) may experience distress when considering consent for a plan with the primary goals of comfort over prolonging life. The SDM(s) may need reassurance that consent for such a plan is not "giving up" on the person. In is not withdrawing care, but rather a change in focus to ensure comfort for a person in their final hours or days.

Frequently asked questions:

See below for FAQs. It you have other questions see the SDM section of the Resource Guide.

What if a person would prefer to have a friend as their SDM rather than a family member?

A person can choose to have a friend as their SDM by appointing them as an Attorney for Personal Care. They will have to complete the legal paperwork for this.

Does an SDM have to follow the person's wishes?

- The SDM must look at any wishes made when a person was mentally capable.

- They must ask themselves two questions:

1) Do they apply to the current decision?

2) Are they possible to follow?

- SDMs do not have to follow a wish that is impossible to honour.

- There are many things that can make a wish impossible to honour. Decisions will depend on the person's health and care needs, finances and the number of people around who can help care for a person.

- For example, a person may tell an SDM that they wish to remain at home but there may be times when a hospital or long-term care

is the best place to receive care based on the person's needs.

How will an SDM make decisions if a person has not had any ACP conversations?

- If a person's wishes are not known, the SDM(s) must act in a person's “best interests.”

- “Best interests” has a specific meaning in law: your SDM must consider a person's values and beliefs.

- They would also consider:

- The person's health condition

- If the person was likely to improve, remain the same or deteriorate without the treatment

- The risks and benefits of the treatment options

Can a person do ACP even if they don't have an SDM?

- Everyone in Ontario automatically has an SDM - you find the automatic SDM on the hierarchy as defined in the Health Care Consent Act.

- If there are no relatives or appointed SDMs, the Public Guardian and Trustee (PGT) will act as SDM if someone is not capable of making healthcare decisions.

- A person can choose to have ACP conversations with their healthcare providers.

- Healthcare provider can share this information with the PGT if they have to make healthcare decisions

What is the difference between an Attorney for Personal Care and an SDM?

An Attorney for Personal Care (POAPC) is one type of SDM.

They are the second highest on the list of SDMs.

What if a person is not happy with their automatic substitute decision-maker?

- If a person is not happy with your automatic SDM, they may appoint an Attorney for Personal Care.

- A person must be capable at the time they appoint an Attorney for Personal Care.

Should a person include their SDM in ACP conversations?

- Yes! It is good idea to involve a person's SDM as much as possible in these conversations.

- ACP is meant to prepare an SDM to make healthcare decisions in the future if a person loses capacity to make those decisions themselves.

- If a person isn't comfortable including their SDM in ACP conversations, think if there might be someone else they would prefer in the role.

- An SDM may have to make some hard choices. Knowing about the person and their values can make this easier.

What if SDM(s) disagree amongst themselves?

If people who are equally entitled to act as SDM(s) cannot agree on the decisions about your treatment, you may have several options depending on your clinical setting:

- Make sure you have explored the underlying illness understanding and underlying reasons behind the disagreement as there may misunderstandings that are leading to the issue.

- If you have access to bioethics consultation, they may be able to support the SDM(s) to reach consensus.

- If you cannot reach agreement among the SDM(s), the Public Guardian and Trustee is required to act as SDM. The Public Guardian and Trustee does not choose between the disagreeing decision-makers but makes the decision instead.

What is the difference between an Attorney for Personal Care and an Attorney for Property?

- A Power of Attorney for Personal Care ONLY gives the person the ability to make decisions about healthcare. They cannot make decisions about your property or finances.

- For property and finances, a person must prepare a Power of Attorney for Property.

- A person does not need to choose the same person for both. Each is appointed in a separate document.

- For more information: